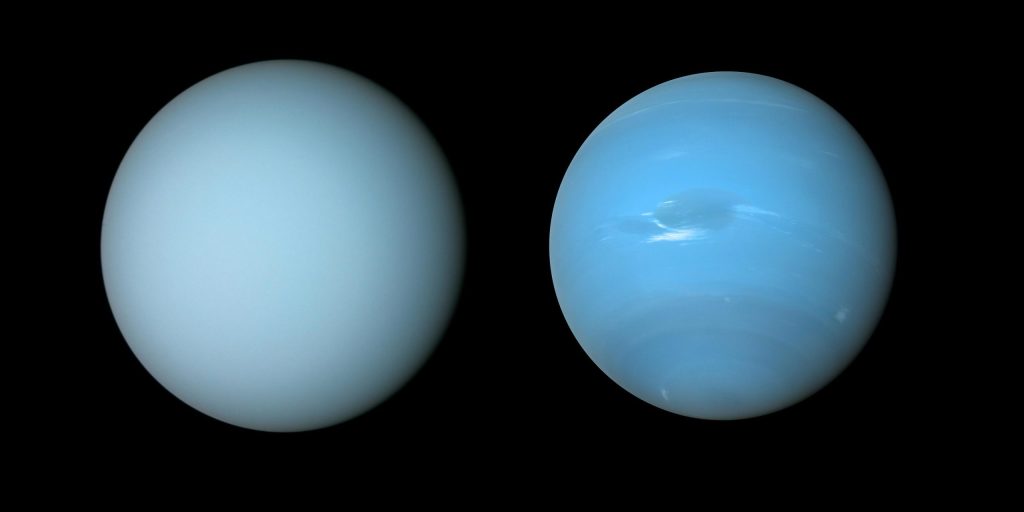

La navicella spaziale Voyager 2 della NASA ha catturato queste viste di Urano (a sinistra) e Nettuno (a destra) durante i sorvoli planetari negli anni ’80. Credito: NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Johnson

Le osservazioni dell’Osservatorio Gemini e di altri telescopi rivelano un’eccessiva foschia[{” attribute=””>Uranus makes it paler than Neptune.

Astronomers may now understand why the similar planets Uranus and Neptune have distinctive hues. Researchers constructed a single atmospheric model that matches observations of both planets using observations from the Gemini North telescope, the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, and the Hubble Space Telescope. The model reveals that excess haze on Uranus accumulates in the planet’s stagnant, sluggish atmosphere, giving it a lighter hue than Neptune.

I pianeti Nettuno e Urano hanno molto in comune – hanno masse, dimensioni e composizioni atmosferiche simili – ma i loro aspetti sono notevolmente diversi. Alle lunghezze d’onda visibili, Nettuno è visibilmente di colore più blu mentre Urano è di una tonalità più chiara di ciano. Gli astronomi ora hanno una spiegazione del perché i due pianeti hanno colori così diversi.

Una nuova ricerca indica che lo strato di foschia concentrata che si trova su entrambi i pianeti è più spesso su Urano rispetto a uno strato simile su Nettuno e “imbianca” l’aspetto di Urano più che su Nettuno.[1] Se non c’è nebbia dentro atmosfera Da Nettuno e Urano, appariranno entrambi più o meno uguali in blu.[2]

Questa conclusione deriva da un modello[3] che un team internazionale guidato da Patrick Irwin, professore di fisica planetaria all’Università di Oxford, ha sviluppato per descrivere gli strati di aerosol nelle atmosfere di Nettuno e Urano.[4] Precedenti indagini sulle atmosfere superiori di questi pianeti si sono concentrate sull’aspetto dell’atmosfera solo a lunghezze d’onda specifiche. Tuttavia, questo nuovo modello, composto da più strati atmosferici, abbina le osservazioni di entrambi i pianeti su un’ampia gamma di lunghezze d’onda. Il nuovo modello include anche particelle sfocate all’interno di strati più profondi che in precedenza si pensava contenessero solo nubi di metano e ghiaccio di idrogeno solforato.

Questo diagramma mostra tre strati di aerosol nelle atmosfere di Urano e Nettuno, come progettato da un team di scienziati guidato da Patrick Irwin. L’altimetro sul grafico rappresenta la pressione superiore a 10 bar.

Lo strato più profondo (strato di aerosol-1) è spesso ed è costituito da una miscela di idrogeno solforato ghiaccio e particelle dall’interazione delle atmosfere planetarie con la luce solare.

Lo strato principale che influenza i colori è lo strato intermedio, che è uno strato di particelle di nebbia (indicato nella carta come lo strato aerosol-2) che è più spesso su Urano che su Nettuno. Il team sospetta che su entrambi i pianeti il ghiaccio di metano si condensa sulle particelle in questo strato, attirando le particelle più in profondità nell’atmosfera mentre cadono le nevi di metano. Poiché l’atmosfera di Nettuno è più attiva e turbolenta di quella di Urano, il team ritiene che l’atmosfera di Nettuno sia più efficiente nel deviare le particelle di metano nello strato di foschia e produrre quella neve. Questo rimuove più foschia e mantiene lo strato di foschia di Nettuno più sottile di quanto non sia su Urano, il che significa che il blu di Nettuno sembra essere più forte.

Sopra entrambi gli strati c’è un esteso strato di nebbia (strato di aerosol 3) simile allo strato sottostante ma più fragile. Su Nettuno, sopra questo strato si formano anche grandi particelle di ghiaccio di metano.

Credito: Gemini International Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA, J. da Silva/NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Johnson

“Questo è il primo modello che si adatta in modo sincrono alle osservazioni della luce solare riflessa dall’ultravioletto al vicino infrarosso”, ha spiegato Irwin, autore principale di un documento di ricerca che presenta questa scoperta nel Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. “E’ anche il primo a spiegare la differenza di colore visibile tra Urano e Nettuno.”

Il modello del team è costituito da tre strati di aerosol a diverse altitudini.[5] Lo strato principale che influenza i colori è lo strato intermedio, che è uno strato di particelle di nebbia (indicato nella carta come lo strato aerosol-2) che è più spesso sopra il Urano del Nettuno. Il team sospetta che su entrambi i pianeti il ghiaccio di metano si condensa sulle particelle in questo strato, attirando le particelle più in profondità nell’atmosfera mentre cadono le nevi di metano. Poiché l’atmosfera di Nettuno è più attiva e turbolenta di quella di Urano, il team ritiene che l’atmosfera di Nettuno sia più efficiente nel deviare le particelle di metano nello strato di foschia e produrre quella neve. Questo rimuove più foschia e mantiene lo strato di foschia di Nettuno più sottile di quanto non sia su Urano, il che significa che il blu di Nettuno sembra essere più forte.

Mike Wong, astronomo presso[{” attribute=””>University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the team behind this result. “Explaining the difference in color between Uranus and Neptune was an unexpected bonus!”

To create this model, Irwin’s team analyzed a set of observations of the planets encompassing ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths (from 0.3 to 2.5 micrometers) taken with the Near-Infrared Integral Field Spectrometer (NIFS) on the Gemini North telescope near the summit of Maunakea in Hawai‘i — which is part of the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab — as well as archival data from the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, also located in Hawai‘i, and the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

The NIFS instrument on Gemini North was particularly important to this result as it is able to provide spectra — measurements of how bright an object is at different wavelengths — for every point in its field of view. This provided the team with detailed measurements of how reflective both planets’ atmospheres are across both the full disk of the planet and across a range of near-infrared wavelengths.

“The Gemini observatories continue to deliver new insights into the nature of our planetary neighbors,” said Martin Still, Gemini Program Officer at the National Science Foundation. “In this experiment, Gemini North provided a component within a suite of ground- and space-based facilities critical to the detection and characterization of atmospheric hazes.”

The model also helps explain the dark spots that are occasionally visible on Neptune and less commonly detected on Uranus. While astronomers were already aware of the presence of dark spots in the atmospheres of both planets, they didn’t know which aerosol layer was causing these dark spots or why the aerosols at those layers were less reflective. The team’s research sheds light on these questions by showing that a darkening of the deepest layer of their model would produce dark spots similar to those seen on Neptune and perhaps Uranus.

Notes

- This whitening effect is similar to how clouds in exoplanet atmospheres dull or ‘flatten’ features in the spectra of exoplanets.

- The red colors of the sunlight scattered from the haze and air molecules are more absorbed by methane molecules in the atmosphere of the planets. This process — referred to as Rayleigh scattering — is what makes skies blue here on Earth (though in Earth’s atmosphere sunlight is mostly scattered by nitrogen molecules rather than hydrogen molecules). Rayleigh scattering occurs predominantly at shorter, bluer wavelengths.

- An aerosol is a suspension of fine droplets or particles in a gas. Common examples on Earth include mist, soot, smoke, and fog. On Neptune and Uranus, particles produced by sunlight interacting with elements in the atmosphere (photochemical reactions) are responsible for aerosol hazes in these planets’ atmospheres.

- A scientific model is a computational tool used by scientists to test predictions about a phenomena that would be impossible to do in the real world.

- The deepest layer (referred to in the paper as the Aerosol-1 layer) is thick and is composed of a mixture of hydrogen sulfide ice and particles produced by the interaction of the planets’ atmospheres with sunlight. The top layer is an extended layer of haze (the Aerosol-3 layer) similar to the middle layer but more tenuous. On Neptune, large methane ice particles also form above this layer.

More information

This research was presented in the paper “Hazy blue worlds: A holistic aerosol model for Uranus and Neptune, including Dark Spots” to appear in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

The team is composed of P.G.J. Irwin (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), N.A. Teanby (School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, UK), L.N. Fletcher (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), D. Toledo (Instituto Nacional de Tecnica Aeroespacial, Spain), G.S. Orton (Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, USA), M.H. Wong (Center for Integrative Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, USA), M.T. Roman (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), S. Perez-Hoyos (University of the Basque Country, Spain), A. James (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), J. Dobinson (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK).

NSF’s NOIRLab (National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory), the US center for ground-based optical-infrared astronomy, operates the international Gemini Observatory (a facility of NSF, NRC–Canada, ANID–Chile, MCTIC–Brazil, MINCyT–Argentina, and KASI–Republic of Korea), Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), the Community Science and Data Center (CSDC), and Vera C. Rubin Observatory (operated in cooperation with the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory). It is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with NSF and is headquartered in Tucson, Arizona. The astronomical community is honored to have the opportunity to conduct astronomical research on Iolkam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) in Arizona, on Maunakea in Hawai‘i, and on Cerro Tololo and Cerro Pachón in Chile. We recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that these sites have for the Tohono O’odham Nation, the Native Hawaiian community, and the local communities in Chile, respectively.

“Giocatore. Aspirante evangelista della birra. Professionista della cultura pop. Amante dei viaggi. Sostenitore dei social media.”

More Stories

SpaceX ha ora fatto atterrare un numero maggiore di razzi booster rispetto alla maggior parte degli altri mai lanciati

Osserva il Sole trascinare brevemente la coda della cometa Satana

SpaceX lancia 23 satelliti Starlink dalla Florida (foto)